Sleep Paralysis as A Spiritual Experience: One Person's Pursuit of Validation Part 1

Stacy Cameron is a young sleep paralysis experiencer who offered to write a guest post for Transcend readers. As a SP experiencer, she seeks answers and support.

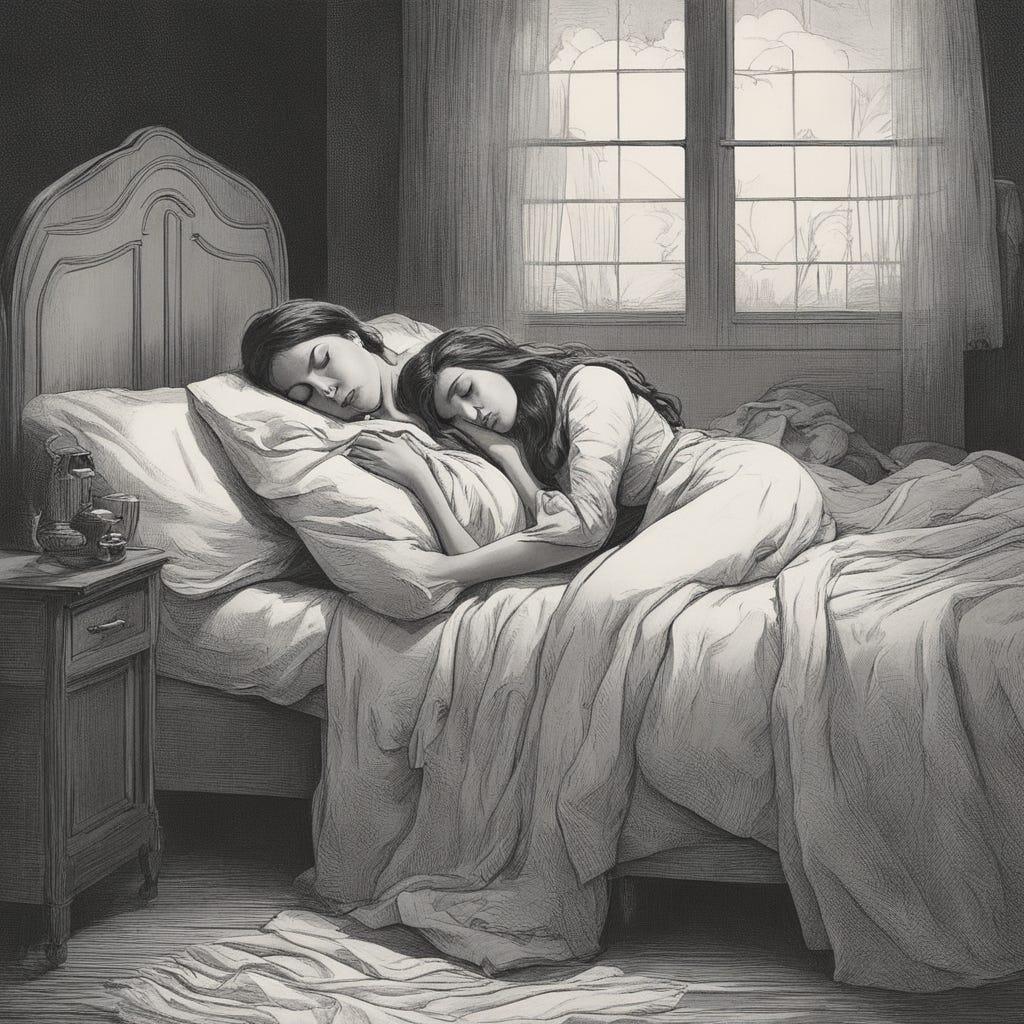

I could hear bubbles inside my ears, a strange sensation - almost electrical. The internal vibration in my mind was so heavy I couldn't lift my head off the pillow. When I opened my eyes, I could see a dark shadow with white eyes staring at me, looming over my sister and me, reaching its arm towards us. I tried to scream for my dad, for my sister to wake up, but my voice was hollow and underwater. I realized I could not move. I thought I had died, that my soul was stuck in this in-between land with something evil trying to take my life. But then I shot awake. Quietly, I went downstairs to sit with my dog. I didn't bother to share this with any adult in my family.

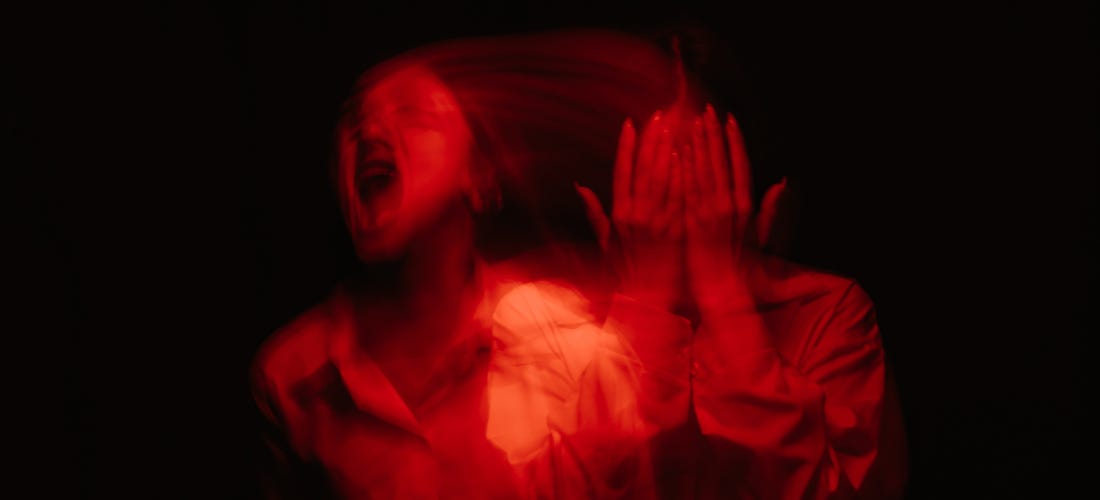

I am twenty-two now, and just like every other night for the last sixteen years, last night I had sleep paralysis (SP). This time I was in a farmhouse, derelict, with a central wooden staircase. Suddenly, a red ball began chasing my sister and me up the stairs. This peculiar supernatural ball kept repeating the word "mum" in a child's voice every time it landed on a step. I grabbed hold of it with so much fear, and my sister froze. "Brooke! What are you doing?" Without a second thought, I threw it back down the stairs. It hit the floor but did not bounce. It was dense. It was as though we had thrown a bowling ball down a well, yet this was clearly some sort of dodgeball based on the distinctive sound it made when it chased us. A horrible sense of dread went through me as I watched it sit so still and lifeless. Both of us started screaming and crying. I immediately needed to get out of this because it was too painful to stay there. I managed to wake up, but I couldn't move my arms, so I fought as hard as I could to wake up.

The next day, I sat searching 'red ball meaning in dreams,' 'What does it mean when you see something inanimate die in your dream?' and 'What did my dream mean?' I was in the middle of a café with my partner discussing his lab work. I was barely present for this conversation. My mind was elsewhere. Am I angry about something? Am I stressed for some reason? I kept this experience to myself. I watched my coffee go cold on the table as my eyes saw through the conversation happening before me. That red ball, the screaming; it is all I can think about.

In current SP research, very little is known about SP hallucinations (Sharpless & Grom, 2014). Simultaneously, no treatments exist for SP, and as a result, the focus has shifted to overcoming this problem by trying to find a robust, reliable preventative solution to these experiences (Sharpless & Grom, 2014). Although society attempts to scientifically explain SP as a disruption in our REM cycles, this is not entirely true for every instance or occurrence of SP (Jalal & Ramachandran, 2014). The body is unreliable for those who suffer from SP; we learn through this experience of fear and paralysis that we can no longer trust our body to move on command. This trust in our bodies is damaged. As a result, just like any other physical or mental illness, this changes our perception of the world and cultivates new fears of 'existential uncertainty' and 'exposure' (Carel, 2016, p. 96). Carel explains how this bodily doubt "challenges the everyday veneer of normality and control that we cultivate as individuals and as a society" (Carel, 2016, p. 96). Perhaps this can explain why those who suffer from SP have a fear of being seen as ‘weird’ (Cheyne, 2003): we realize this experience makes us different and separate from others. Therefore, it is now too difficult to trust what we once knew or thought about our bodies.

We can add another layer to Carel's argument and suggest that this bodily doubt is even harder to endure when the experience of paralysis is separate from the version of us that exists. In reality, we did not experience paralysis because our bodies were asleep, preventing us from waving our arms around while we dream. Yet, our experiences were real in how we believe we experienced paralysis. When these dark shadows present themselves to us, we learn the body is weak and barely contains the strength to save us from danger.

How can you communicate this intricate relationship with body and mind when the relationship is... mind and mind? This is why most refuse to visit a healthcare provider for these experiences (Muzammil et al., 2023). It is an impossible task to explain the subjective experience of SP with any meaningfulness attached to the experience with anyone. Carel states this meaningfulness attributed to bodily doubt makes sense, "the meaning is doubt itself" (Carel, 2016, p. 94). In this particular case, the experience of paralysis, with an added layer of hallucination to explain this paralysis, with the knowledge that this experience in reality never occurred, is incredibly difficult to explain and describe. It is too easy to subject yourself to the high likelihood that other people could simply deny this experience because it never occurred. But it did. So, what now?

As each of us in our own way seeks answers to the many questions that life presents us with, Stacy has openly added to the SP debate her honest views. Look out for the 2nd part of this post.

Thank you for reading this post.

I’m Sheila Pryce Brooks, and if you are reading this, you are already on your journey. I’ll be back soon.

**If you’d like detailed references send me an email: substack@sheilaprycebrooks.com

Services

If you would like to speak to me about your sleep paralysis find out how ‘HERE’

Find out more about me:

Website: sheilaprycebrooks.com

If you enjoyed this issue, please subscribe (if you are not already subscribed). Every subscription helps the community grow and supports me, as a creator.